Using Standard Train Signals

By Maurice Lewman

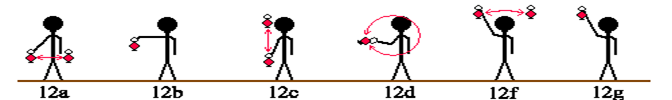

Before radios, each train was like an island. Once you had permission to leave a point, the crew operated as a unit, separate from other trains except by train orders or signal indication. If trouble developed it was taken care of on the spot. Whatever was necessary to fix the problem was done. If a telephone was near, we notified the dispatcher of the problem.When railroading started, the crew could speak to each other about train operation. But as trains grew in length, it became apparent that the ground man was going to do a lot of walking to get instructions. Hand signals were the next move. This worked fine and when trains started running at night, day signals had to be converted to a light, to give the same indication as a day indication. They finally had six standard hand and light signals. Of course there are many signals besides these that the men on each railroad developed for their particular needs. Here are the six standard signals:

Rule 12a, stop. [Swung horizontally at right angle to the track.] This is sometimes

called a swing down. The reason for that name is the brakeman is going from a reduced speed

hand signal, (or the word “easy” if the fireman was relaying the signal to the engineer), to

the hand stop signal.

Rule 12b, reduced speed. [Held horizontally at arms length.] This signal is used previous to the stop signal 12a. It also is used if the engine was shoving cars and the brakeman wanted to slow down approaching a road crossing or any reason to slow the movement down, usually followed by a proceed signal if the way was clear. As already quoted, this was usually called out as “easy.” The “easy” signal was given based on the cuts speed and distance from the car or place you wanted to stop. A few brakemen could judge speed and distance as a fine art. If you followed their signals you could couple to a car or another cut with a passenger-train coupling (that means gently.)

Rule 12c, proceed. [Raised and lowered vertically. A smaller, slower motion signals a slower speed.] I call this the bye-bye signal. Giving this was like waving goodbye to someone. The farther you were from the engine the larger this or any signal had to be. If you were at the rear of the engine it meant go ahead, in relation to the direction the engine was headed. If you were in front and you waved bye bye, that meant come ahead per the direction of the engine.

Rule 12d, back. [Swung vertically in a circle, at right angle to the track. A decreasing arc and slower motion signals a slower speed.] Back was like proceed. It was determined by forward or backward on the unit where the engineer was located. This signal was given in a circle, small close, larger far away. If the brakeman was some distance away, say sixty car lengths, in daylight he would pick up a piece of scrap paper, if in car shadows and give a signal. To make a move a short distance, the signal would be given in a large circle but slowly. This determined speed and distance to the move. A circle at a speed between slow and fast would naturally be for a normal switching speed move. Each brakeman's signals were like a written signature. You could tell who was giving the signal by the way the signal was given.

Rule e, not used now because the length of trains voided its use. It was a train-parted signal

Rule f, apply airbrakes. [Swung horizontally above the head, when train is standing.] It is used in air brake tests. The hand or light swung horizontally above the head tells the engineer to apply the brakes. This is in the yards or on the road.

Rule g, release air brakes. [Held at arm's length above the head, when train is standing.] Notice this is a small g. The hand or light held above the head tells the engineer to release the brakes.

Rule h. I will have to make it seven rules instead of six. Rule h states, any object waved on or near the track is a signal to stop. Also included (as hand signals) is the proper use of flares.

There were many variations of these signals. Most of the time, the stop signal was given as described in the text. Sometimes the brakeman might misjudge speed or distance. As he realizes this he will give an excited stop. If it is going to be a real hard coupling, the trainman would swing down, leap from the car and give a panic stop with both arms. In the engine cab, you braced yourself and told the fireman to "Hang on, he is trying to fly." You adapt to each crew's way of giving signals. Hand signals were part of the fireman's training.

While I was still working, the radio traffic would be very heavy. We had two channels and they would be so busy that sometimes we would have to wait until they slowed down to be able to talk to the dispatcher or yardmaster to make our moves. After we had permission and the radio traffic was still heavy, I would get the trainman's attention and we would work by hand signals until the radio traffic slowed down. Hand signals were basically safer than radio and less time consuming in busy radio conditions. I know this is going to spark an argument, but remember what I said about each crew being an island. With hand signals each crew was isolated from other crews. With the radio all crews are in a mix. When radio traffic is low things are okay but as traffic increases, safety becomes a problem to deal with.

As I started to write this, I thought, "Would it be interesting to anyone?" About this time a friend asked me how we communicated before radios. I hope this helps the younger generation understand why there were four and five men on the crews and a caboose on the end of the train.

Editor’s note: Could use these hand signals while operating our trains at operating sessions?